In part 1, we introduced the maddening story of buying shoes in a fictitious deregulated shoe size industry. It doesn't take a large stretch of imagination to see that the setup for the shoe story is an appropriate analogy for AFS heads. Simply substitute your foot size with your Spey rod and your fitting shoe size with your matching Spey line (using the differing shoe colors for differing sink heads) and the connection is made.

My affinity for AFS heads largely comes from the ability to change the sink rate of the entire shooting head, giving me a much tunable sink rate to match differing depth presentation for various combination of fly and on-stream factors. So, my first step in properly loading the rod of choice, a Zpey 12'3" #8 EU class rod, was to find a proper loading AFS floating head. Although the rod lists a grain window of 338 to 416 grains, just like the process of finding the light colored shoe, I had to experiment with several heads; sometimes using heavier heads that came with truncated tips (perhaps in attempts to keep the weight within the rod's grain window) [footnote 1]. I eventually settled for a 400 grain AFS #7 floating head. This floating head discovery is akin to the light colored shoe process.

My affinity for AFS heads largely comes from the ability to change the sink rate of the entire shooting head, giving me a much tunable sink rate to match differing depth presentation for various combination of fly and on-stream factors. So, my first step in properly loading the rod of choice, a Zpey 12'3" #8 EU class rod, was to find a proper loading AFS floating head. Although the rod lists a grain window of 338 to 416 grains, just like the process of finding the light colored shoe, I had to experiment with several heads; sometimes using heavier heads that came with truncated tips (perhaps in attempts to keep the weight within the rod's grain window) [footnote 1]. I eventually settled for a 400 grain AFS #7 floating head. This floating head discovery is akin to the light colored shoe process.

The next step was to find a sinking line. At that time, the only AFS sinking head was the Sink 4 (S4) head, tapered and weight balanced similarly to the floating version. Although Rio only offered this head in the #7/8 class category as the lightest head, weighing 460 grains, I found this line one of the most satisfying combination I enjoy casting over and over again (footnote 2). This is even after I had to cut back and substitute the last 8' of the head on the fly end with a #7, 10' Density Compensated type 6 tip (footnote 3). I enjoy the smooth accelerating turnover as well as the well match loading characteristics. My cast becomes one that has a non rushed forward cast and a fast recovery tip for prodigious distance while casting weighted flies. This S4 discovery is akin to the semi-dark shoe process.

But the biggest shocker was making the 'black shoe' purchase when fine tuning the Sink2/Sink 3 (S2S3 hereafter) head. Hey, if the #6/7 floater works, the blind obedience here is to get a #6/7 S2S3 head. But casting a #6/7 S2S3 head with the Zpey rod was a woefully underloaded and dissatisfying rod/ line combination. Yes, I was tiring myself quickly from not getting the proper rod bend. Fortunately, I contacted and arranged with Rio exchanging the under loading head (and several classes between #6/7 and #10/11 over several exchanges [footnote 4]) until I finally settled for the #10/11 head weighing 640 grains (footnote 5). This calculates to a 240 grain difference between the successful #6/7 floating and the final #10/11 S2S3 head, a woeful difference impossible to overlook. Even so, this final choice was an approximation at best because I could not modify the S2S3 head (or this would render it unreturnable) nor add any sinking leaders without grossly exceeding the maximum cast-able length (3 times rod length, water borne anchor, sinking head). Agh, more fine tuning with leaders/ cutting the butt end that could go either way in terms of proper loading. Mystery behind door # 3 awaits me with some unpredictability.

Because of this weight class jump from #6/7 (floating) to 7/8 (S4) to 10/11 (S2S3), I started to see that an allegiance to the floating weight class of #6/7 throughout the whole sink spectrum would not have led to a satisfying rod/ line result. Rather, the true line/rod performance now makes this weight class designation a misleading criteria. Huh, but why even have a weight class at all if this weight class is misleading?

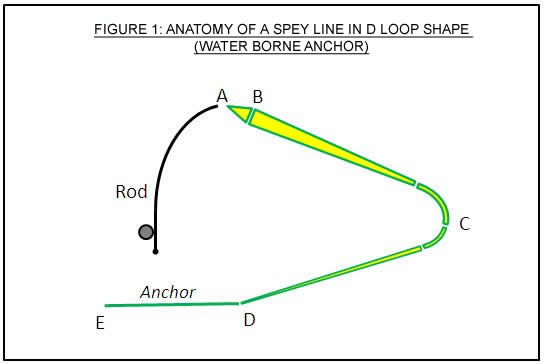

While I got thinking what is the hidden reality untold by the standardizing effect of weight class, I remembered a diagram from Henrik Mortensen's 'Fly Casting Scandinavian Style' book. His diagram suggested that the portion of the line that loads the rod, the Active Line, is from the rod tip to the apex of the D loop. This corresponds to section from A to C in the Figure 1 below.

But the biggest shocker was making the 'black shoe' purchase when fine tuning the Sink2/Sink 3 (S2S3 hereafter) head. Hey, if the #6/7 floater works, the blind obedience here is to get a #6/7 S2S3 head. But casting a #6/7 S2S3 head with the Zpey rod was a woefully underloaded and dissatisfying rod/ line combination. Yes, I was tiring myself quickly from not getting the proper rod bend. Fortunately, I contacted and arranged with Rio exchanging the under loading head (and several classes between #6/7 and #10/11 over several exchanges [footnote 4]) until I finally settled for the #10/11 head weighing 640 grains (footnote 5). This calculates to a 240 grain difference between the successful #6/7 floating and the final #10/11 S2S3 head, a woeful difference impossible to overlook. Even so, this final choice was an approximation at best because I could not modify the S2S3 head (or this would render it unreturnable) nor add any sinking leaders without grossly exceeding the maximum cast-able length (3 times rod length, water borne anchor, sinking head). Agh, more fine tuning with leaders/ cutting the butt end that could go either way in terms of proper loading. Mystery behind door # 3 awaits me with some unpredictability.

Because of this weight class jump from #6/7 (floating) to 7/8 (S4) to 10/11 (S2S3), I started to see that an allegiance to the floating weight class of #6/7 throughout the whole sink spectrum would not have led to a satisfying rod/ line result. Rather, the true line/rod performance now makes this weight class designation a misleading criteria. Huh, but why even have a weight class at all if this weight class is misleading?

While I got thinking what is the hidden reality untold by the standardizing effect of weight class, I remembered a diagram from Henrik Mortensen's 'Fly Casting Scandinavian Style' book. His diagram suggested that the portion of the line that loads the rod, the Active Line, is from the rod tip to the apex of the D loop. This corresponds to section from A to C in the Figure 1 below.

So far, I have found that the best explanation I can come up with is that the apparent resistance from the THREE (3) differing weight class heads must be, or at least perhaps, close to each other. That means the load the rod experiences, whether with the 400 grain floater or the 640 grain S2S3 sinker, is approximately equivalent for my current casting style.

Henrik suggested that the section A to C is the dominant portion that loads the rod. He calls it the 'active line'. It is the portion of the line the rod tip feels as a load during the forward cast. With this and with a reliable grain scale, I performed a quick calculation between the THREE (3) scenarios, using some geometric assumptions (footnote 6), and found that the head- although they are remarkably different in overall weight- all calculate to roughly the same active line load. Perhaps this now 'active line load' is the unifying common reality behind them, a story that is simply not told by merely looking at weight class. This story is reinforced further when the active line sections all calculate out to be between 300 to 310 grains.

Remember the shoe story and the deregulated shoe size? Just as with the shoe, this discovery churned up some stumbling blocks that made the floater weight class unusable when selecting the S4 or even more worse for the S2S3 head. These stumbling blocks are 1) Leader Effect, 2) Weight Distribution Effect.

Referencing the above figure 1 again, the Leader Effect basically has more of the head in the active line zone (section A to C) than when casting without a leader. With Leader DE as the Anchor in play, the entire head AD is aerialized as a D loop, with C as the apex. But when anchor DE is absent when casting with sink heads, part of section CD has to become the new anchor. The Leader Effect becomes more obvious when we see that the recommended total length for a floating head/ leader system is 4.2 times the rod length (footnote 7), but only 2.3- 2.7 times the rod length for sinking heads/ tips. Since 4.2 is larger than 2.X, length AC is longer for the floater than the sinker, pushing more of the floating head into this active loading zone. Hey, there is a simple way to verify this. Simply cast your floating head with and without a leader, and your load- sans blowing your anchor with proper control and timing- will be woeful less for the latter. My #6/7 floater with a 3' leader is the closest thing to replicating a non-existent #6/7 S4 head (the 3' leader is to to keep apples to apples comparison with my #7/8 AFS S4) .

The next stumbling block is strictly a creature of line design. Both the floating and Sink 4 heads are part of the Generation 1 AFS family. They are somewhat triangular tapered made out of homogenous (constant density) material (see figure 2 below). Thus, their weight distribution is identical, with Gen. 1 being rear centric. Although not a problem for the floater, this rear centricity posed a down side for the now-discontinued S4 head: the butt end was sinking faster than the tip end, an undesirable feature for actual fishing conditions. So, Rio introduced Generation 2 Sink AFS heads, a dual density head with a faster sinking tip than the butt end. But in order for the tip to sink faster, the Gen. 2 design had to re-balance the head with a design that is now level-line centric (see figure 3 below) [footnote 8]. This breaking rank with Gen. 1 rear centricity means what was casting good in Gen 1 may no longer be true when casting Gen. 2 heads, both using the same weight class. Hey, a quick way I proved for myself was to simply connect your Windcutter body with a 10 and 5 foot cheater, totaling 400 grains at 38', and cast it (footnote 9). I found this setup to be rather clunky in turnover, and even more dissatisfying in loading than the earlier mock AFS 6/7 S4 head, both products largely from the level-line centric weight balance.

Henrik suggested that the section A to C is the dominant portion that loads the rod. He calls it the 'active line'. It is the portion of the line the rod tip feels as a load during the forward cast. With this and with a reliable grain scale, I performed a quick calculation between the THREE (3) scenarios, using some geometric assumptions (footnote 6), and found that the head- although they are remarkably different in overall weight- all calculate to roughly the same active line load. Perhaps this now 'active line load' is the unifying common reality behind them, a story that is simply not told by merely looking at weight class. This story is reinforced further when the active line sections all calculate out to be between 300 to 310 grains.

Remember the shoe story and the deregulated shoe size? Just as with the shoe, this discovery churned up some stumbling blocks that made the floater weight class unusable when selecting the S4 or even more worse for the S2S3 head. These stumbling blocks are 1) Leader Effect, 2) Weight Distribution Effect.

Referencing the above figure 1 again, the Leader Effect basically has more of the head in the active line zone (section A to C) than when casting without a leader. With Leader DE as the Anchor in play, the entire head AD is aerialized as a D loop, with C as the apex. But when anchor DE is absent when casting with sink heads, part of section CD has to become the new anchor. The Leader Effect becomes more obvious when we see that the recommended total length for a floating head/ leader system is 4.2 times the rod length (footnote 7), but only 2.3- 2.7 times the rod length for sinking heads/ tips. Since 4.2 is larger than 2.X, length AC is longer for the floater than the sinker, pushing more of the floating head into this active loading zone. Hey, there is a simple way to verify this. Simply cast your floating head with and without a leader, and your load- sans blowing your anchor with proper control and timing- will be woeful less for the latter. My #6/7 floater with a 3' leader is the closest thing to replicating a non-existent #6/7 S4 head (the 3' leader is to to keep apples to apples comparison with my #7/8 AFS S4) .

The next stumbling block is strictly a creature of line design. Both the floating and Sink 4 heads are part of the Generation 1 AFS family. They are somewhat triangular tapered made out of homogenous (constant density) material (see figure 2 below). Thus, their weight distribution is identical, with Gen. 1 being rear centric. Although not a problem for the floater, this rear centricity posed a down side for the now-discontinued S4 head: the butt end was sinking faster than the tip end, an undesirable feature for actual fishing conditions. So, Rio introduced Generation 2 Sink AFS heads, a dual density head with a faster sinking tip than the butt end. But in order for the tip to sink faster, the Gen. 2 design had to re-balance the head with a design that is now level-line centric (see figure 3 below) [footnote 8]. This breaking rank with Gen. 1 rear centricity means what was casting good in Gen 1 may no longer be true when casting Gen. 2 heads, both using the same weight class. Hey, a quick way I proved for myself was to simply connect your Windcutter body with a 10 and 5 foot cheater, totaling 400 grains at 38', and cast it (footnote 9). I found this setup to be rather clunky in turnover, and even more dissatisfying in loading than the earlier mock AFS 6/7 S4 head, both products largely from the level-line centric weight balance.

Thus, when one tries to cross over from AFS Gen. 1 floating heads to AFS Gen. 2 Dual density heads, the hazards of Leader Effect and Weight Distribution Effect makes this cross over much like the fictitious shoe store experience when trying, but eventually failing, to use an earlier size for darker shoes. But these hazards from such crossing can be neutralized with a simple bridge that tells a hidden 'Active Line Load', a reality that is masked by the misleading facade of weight class. Knowledge is power, and in this case the power to go beyond the blind obedience of weight class that, while simple in its use, simply cast a false sense of safety.

Footnote:

1) The rod was sent to me with a AFS #7/8 floating head with the tip cut back. But as I progressively got better at casting, I found one weight class below gave me more consistent loops based on my casting style (for now).

2) I initially settled for a #8/9 AFS Sink 4 head, weighing 520 grains. But the final #7/8 weight class became a better fit as I became a more proficient caster that loaded the rod properly with this lower weight choice.

3) This modification was needed to overcome the fact that the butt section was sinking faster than the tip section due to the non- density compensated properties of a tapered but homogenous density head.

4) This several exchanges allowed me to do some weight balance comparison, leading a line change recommendation to Rio (click here for pdf report [to be released soon]).

5) I opted for this #10/11 weight class (to be reused for a 14 foot #9/10 rod) although my latest casting evolution suggest I could drop down one or perhaps two weight class for the Zpey rod. But even still this drop down still means a 120 grains heavier than the #6/7 floater.

6) I approximated that the active line weight is the butt end (starting with A in figure 1) weight of 50% of total line system length (tips and leaders included). For a floating head, I approximated that 1/3 of the leader length needs to be subtracted before calculating the butt end weight of the 50% of this now shortened length.

7) The head length is 2.7 times, the leader is 1.5 times rod length.

8) Although this surrogate AFS diagram from Guideline Power taper shows a multi-step down design, the level-line weight distribution is still in effect as the density increases from the thicker butt section to the thinner tip section (the darker the color, the higher the density).

9) One possible recipe for making a Level-line centric 400 grain 38 foot head: Windcutter 6/7/8 Body (23', 230 gr.) + Skagit Cheaters 6/7/8 (5' [60 gr.] + 10' [116 gr.]). The 38 foot length mimics the length I currently use for my final S2S3 setup.

Footnote:

1) The rod was sent to me with a AFS #7/8 floating head with the tip cut back. But as I progressively got better at casting, I found one weight class below gave me more consistent loops based on my casting style (for now).

2) I initially settled for a #8/9 AFS Sink 4 head, weighing 520 grains. But the final #7/8 weight class became a better fit as I became a more proficient caster that loaded the rod properly with this lower weight choice.

3) This modification was needed to overcome the fact that the butt section was sinking faster than the tip section due to the non- density compensated properties of a tapered but homogenous density head.

4) This several exchanges allowed me to do some weight balance comparison, leading a line change recommendation to Rio (click here for pdf report [to be released soon]).

5) I opted for this #10/11 weight class (to be reused for a 14 foot #9/10 rod) although my latest casting evolution suggest I could drop down one or perhaps two weight class for the Zpey rod. But even still this drop down still means a 120 grains heavier than the #6/7 floater.

6) I approximated that the active line weight is the butt end (starting with A in figure 1) weight of 50% of total line system length (tips and leaders included). For a floating head, I approximated that 1/3 of the leader length needs to be subtracted before calculating the butt end weight of the 50% of this now shortened length.

7) The head length is 2.7 times, the leader is 1.5 times rod length.

8) Although this surrogate AFS diagram from Guideline Power taper shows a multi-step down design, the level-line weight distribution is still in effect as the density increases from the thicker butt section to the thinner tip section (the darker the color, the higher the density).

9) One possible recipe for making a Level-line centric 400 grain 38 foot head: Windcutter 6/7/8 Body (23', 230 gr.) + Skagit Cheaters 6/7/8 (5' [60 gr.] + 10' [116 gr.]). The 38 foot length mimics the length I currently use for my final S2S3 setup.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed